This is a continuation of our last post, “What Is & Isn’t Being Said: 8. Systemic Racism & the Narrow Spirituality of the Church.”

Meanwhile, a very different understanding of the mission and role of the Church had grown up in the United States. From the time African Americans began forming their own churches and denominations in the 18th century—due to abuse, violence, persecution, and egregious violations of the Communion of the Saints—they consistently rejected this narrow spirituality view, and for what should be very obvious reasons. The hypocrisy of the American Church was never lost on African Americans, whether slave or free, nor the spuriousness of their truncated “gospel.”

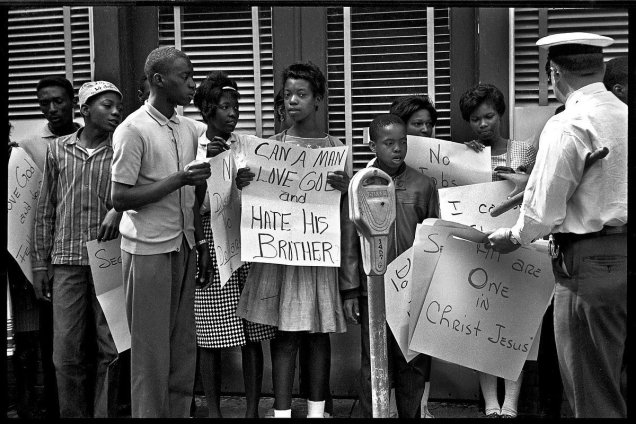

The NSoC Hypocrisy Noticed

In his autobiography, From Slave Cabin to the Pulpit, Rev. Peter Randolph (1825 – 1897) writes,

MANY say the Negroes receive religious education—that Sabbath worship is instituted for them as for others, and were it not for slavery, they would die in their sins—that really, the institution of slavery is a benevolent missionary enterprise. Yes, they are preached to, and I will give my readers some faint glimpses of these preachers, and their doctrines and practices.

After describing the anemic message of the men who preached to the slaves, their hypocritical actions, their segregated churches, and their prowess with a strap of bull hide, Rev. Randolph concluded:

The like of this is the preaching, and these are the men that spread the Gospel among the slaves. Ah! such a Gospel had better be buried in oblivion, for it makes more heathens than Christians. Such preachers ought to be forbidden by the laws of the land ever to mock again at the blessed religion of Jesus, which was sent as a light to the world. […] After such preaching, let no one say that the slaves have the Gospel of Jesus preached to them. (See, “Rev. Peter Randolph: The ‘Gospel’ of the Slave Master and the ‘Benevolence’ of Slavery”)

But none, to my lights, have expressed the grave hypocrisy resulting from Narrow Spirituality better than Frederick Douglas:

We have men-stealers for ministers, women-whippers for missionaries, and cradle-plunderers for church members. The man who wields the blood-clotted cowskin during the week fills the pulpit on Sunday, and claims to be a minister of the meek and lowly Jesus. The man who robs me of my earnings at the end of each week meets me as a class-leader on Sunday morning, to show me the way of life, and the path of salvation. He who sells my sister, for purposes of prostitution, stands forth as the pious advocate of purity. He who proclaims it a religious duty to read the Bible denies me the right of learning to read the name of the God who made me. He who is the religious advocate of marriage robs whole millions of its sacred influence, and leaves them to the ravages of wholesale pollution. The warm defender of the sacredness of the family relation is the same that scatters whole families,—sundering husbands and wives, parents and children, sisters and brothers,—leaving the hut vacant, and the hearth desolate. We see the thief preaching against theft, and the adulterer against adultery. We have men sold to build churches, women sold to support the gospel, and babes sold to purchase Bibles for the poor heathen! all for the glory of God and the good of souls! The slave auctioneer’s bell and the church-going bell chime in with each other, and the bitter cries of the heart-broken slave are drowned in the religious shouts of his pious master. Revivals of religion and revivals in the slave-trade go hand in hand together. The slave prison and the church stand near each other. The clanking of fetters and the rattling of chains in the prison, and the pious psalm and solemn prayer in the church, may be heard at the same time. The dealers in the bodies and souls of men erect their stand in the presence of the pulpit, and they mutually help each other. The dealer gives his blood-stained gold to support the pulpit, and the pulpit, in return, covers his infernal business with the garb of Christianity. (Life of an American Slave [1845])

The African American Church and the NSoC

African American believers and churches had seen the Narrow Spirituality of the Church (NSoC) at work in their own lives, granting cover to their oppressors, allowing their oppressors to live free of the Church’s condemnation. White churches simply did not see it as within the sphere of the Church to meddle in such political and economic matters. They were only commissioned to preach the “gospel” and administer the sacraments. Again, in the words of Dr. Martin King from the last post, “those are social issues, with which the gospel has no real concern.” Those who held all the power—whether social, political, legal, economic, or ecclesial—also believed the Church had no commission from God to question, let alone discipline, their own civic practices, especially when it came to slavery.

On the other hand, the powerless who suffered under the white man’s “Christian” governance had no difficulty seeing the Biblical mandate for Church action on behalf of the oppressed, nor trouble seeing its mandated rebuke of the oppressor. And not only was this their studied Biblical conviction, it was a matter of pure necessity, even survival. To be frank, African Americans needed the Church in a way that most white Americans, both then and now, have little tactile comprehension of.

Who else was to speak for them? Where would their poor go for relief? Where could they meet for safety? Where could their homeless find shelter? Where and with whom could they organize? What other organization in the social atmosphere of race-based slavery and Jim Crow had any interest in defending their rights before kings and hostile citizens? As such, W. E. B. Du Bois describes a church community at the turn to the 20th century far removed from the Narrow Spirituality of Southern conservatives:

The Negro church of today is the social centre of Negro life in the United States, and the most characteristic expression of African character. Take a typical church in a small Virginia town: it is the ‘First Baptist’[…]. This building is the central club-house of a community of a thousand or more Negroes. Various organizations meet here,—the church proper, the Sunday-school, two or three insurance societies, women’s societies, secret societies, and mass meetings of various kinds. Entertainments, suppers, and lectures are held beside the five or six regular weekly religious services. Considerable sums of money are collected and expended here, employment is found for the idle, strangers are introduced, news is disseminated and charity distributed. At the same time this social, intellectual, and economic centre is a religious centre of great power. Depravity, Sin, Redemption, Heaven, Hell, and Damnation are preached twice a Sunday after the crops are laid by; and few indeed of the community have the hardihood to withstand conversion. Back of this more formal religion, the Church often stands as a real conserver of morals, a strengthener of family life, and the final authority on what is Good and Right.

Thus one can see in the Negro church to-day, reproduced in microcosm, all the great world from which the Negro is cut off by color-prejudice and social condition. (“Of the Fathers”; italics mine).

The Presbyterian African American Witness

Lest we be tempted to think otherwise, even conservative Calvinist African American ministers refused to limit the mission of the Church or the scope of its Gospel to Southern standards. Presbyterian minister Rev. Francis J. Grimke (1857 – 1937), supplied the following rebuke from the floor of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in 1888; a speech quite contrary to Thornwell’s address in 1859:

It is important, it seems to me, not only in dealing with race prejudice, but in dealing with every other evil, that Christian men and women should understand, that Christianity is not clay in the hands of the world-spirit to be moulded by it; but is itself to be the moulder of public sentiment and everything else. It isn’t the meal, but is the leaven put into the meal that is to leaven the whole lump. It is salt—not salt that has lost its savor, but the salt of the earth that is intended to arrest corruption, to put an end to the forces that mean moral decay, that tend to break down the tissues of the spiritual life, and to degenerate into festering sores of race prejudice and all the other brood of evils that grow out of it. The mission of the church, of Christian men and women is to mould, not be moulded by encircling influences of evil. To the shame of the millions of white Christians in this land, the brother in black is still a social and religious outcast. (The Works of Francis Grimke, p. 471)

A sound Gospel preacher as well as an ardent social agitator, Grimke called the Church to militancy against racial prejudice:

Where are the forty million professing Christians in this land? The so-called Christian Church, that ought to have the greatest influence in moulding public sentiment in the right direction; that ought to be the greatest militant force against evil (and what greater evil is there than race prejudice?) is resting on its arms, is doing nothing, or comparatively nothing to arrest the evil and to lift up the true standard of brotherhood. (p. 613)

The fact that in Christian America, in this land that is rolling up its church members by the millions, race prejudice has gone on steadily increasing, is a standing indictment of the white Christianity of this land—an indictment that ought to bring the blush of shame to the faces of the men and women, who are responsible for it, whose silence, whose quiet acquiescence, whose cowardice, or worse whose active cooperation, have made it possible. The first thing for the church to do, I say, is to wake up to the fact that it can do something. (p. 464)

The fact is, the Southern conservative proponents of the Narrow Spirituality of the Church never did wake up to this fact; not in Grimke’s lifetime, nor in the Civil Rights era that would follow.

At the height of the Civil Rights movement, another conservative Presbyterian minister, in fact a minister in J. Gresham Machen’s own denomination, Rev. C. Herbert Oliver also upbraided the Church for its participation in segregation, opposition to integration, and ahistorical and non-Calvinistic commitment to the NSoC. He concluded his brilliant article in the July-August 1964 issue of The Presbyterian Guardian with a final plea to his white brothers in the Church:

It is always the duty of God’s people to be a light to the world. There are no considerations that can relieve us of this responsibility. Too often one hears from the white minister such sentiments as, “I know what ought to be done, but if I try to do anything I’ll get put out of my church and they will get an extremist.” This approach does not relieve the minister of his obligation to do what he knows he ought to do.

Nor is the honor of the church upheld by silence in the face of injustice, nor is the true church preserved by failure to do what it knows to be right. The church in Germany did not save itself by its silence in the face of Hitler’s budding inhumanities, but it might have saved Germany if it had preached without fear the biblical concepts of justice and righteousness in the church and in the state. We cannot preserve the church. That is God’s responsibility. Our task is to do what God requires of us—to do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with God. (p. 94)

Where Do We Stand Now?

Sadly, in an interview published nearly 50 years later (June 25, 2013), Rev. Oliver reports that not much had substantially changed over the intervening years:

I’ve also not seen any basic racial changes for the better in the church. I’m sorry to say that, but I ran into the same racism in the PCUSA church as I found in the OPC. When I graduated from seminary, there was no place for me to serve. There were plenty of churches that were vacant, but none of them would call me. It was understood by the higher-ups in the church that there was no future for me being called to a white church. That’s when the call came to me to serve in Maine, and I accepted that and went there and served. But the racial divide in America is still as strong as it was in the 40’s and 50’s. Just more polite, but it is no less real, no less firm, and no less impregnable. (“Grace Through Hardship”)

I would suggest, especially within conservative evangelicalism, Presbyterianism in particular, that the continued, even growing, commitment to a Narrow Spirituality of the Church has contributed much to this lack of change. When slavery passed, the NSoC lived on and became an ecclesial shield for legal and de facto Jim Crow; when Jim Crow passed, the NSoC lived on and continued to serve the same function for color-blind systemic racism as it had for slavery, muzzling the American Church’s prophetic voice in the face of continued church segregation, vast and disturbing social and economic disparities, and encouraging harsh opposition to reconciliation efforts.

And as it stands today, we continue to hear and read the same appeal to Narrow Spirituality from those who have taken up the offensive against so-called “social justice.” Pastor John MacArthur wrote in his discontinued series on Social Justice and the Gospel that,

[…] occasionally a new threat to the simplicity or clarity of the gospel seems to erupt with stunning force and suddenness. The current controversy over “social justice” and racism is an example of that. (“Is the Controversy over ‘Social Justice’ Really Necessary?”)

The message of social justice diverts attention from Christ and the cross. It turns our hearts and minds from things above to things on this earth. It obscures the promise of forgiveness for hopeless sinners by telling people they are hapless victims of other people’s misdeeds.(“The Injustice of Social Justice”)

Jerry Falwell, Jr., president of Liberty University, also gave a nod to the NSoC while defending his own support of Donald Trump in a recent interview:

There’s two kingdoms. There’s the earthly kingdom and the heavenly kingdom. In the heavenly kingdom the responsibility is to treat others as you’d like to be treated. In the earthly kingdom, the responsibility is to choose leaders who will do what’s best for your country. Think about it. Why have Americans been able to do more to help people in need around the world than any other country in history? It’s because of free enterprise, freedom, ingenuity, entrepreneurism and wealth. A poor person never gave anyone a job. A poor person never gave anybody charity, not of any real volume. It’s just common sense to me. (“Jerry Falwell Jr. can’t imagine Trump ‘doing anything that’s not good for the country’”)

And the most typical NSoC arguments continue to come from Reformed and Presbyterian folks like, e.g., Westminster Seminary Professor R. Scott Clark. He writes,

Read on its own terms, the teaching of the New Testament about the Kingdom of God is remarkably silent about the pressing social concerns of the day. Social issues do intrude into the visible church in the NT but none of the Apostles prescribed social or civil remedies for them. They never commented on Nero’s abuses or upon Claudius’ policies. In the NT, Christians are taught how to think about their place in the world but they are never exhorted to flee the world into monasteries nor are they instructed how to transform it. […] The church, as a visible institution, as the embassy of the Kingdom of God and the Kingdom of Heaven, has no social agenda for the wider civil and cultural world.(“The Gospel is not Social”)

Christians have the freedom to participate in civil life, to seek equity, to seek protection from abuse and prejudice (especially in the public, tax-funded sphere). I doubt that the visible, institutional church has any mandate to speak to these issues. There is simply no clear or compelling evidence in the New Testament to support the claim that the visible church must campaign for social justice. (“Racism and the Second Use of the Law”)

And Machen biographer and OPC historian D. G. Hart writes much the same:

Christian teaching on salvation transcends the politics and economics, which likely explains why Paul had so little to say about the social injustice of the Roman Empire. Christianity is an otherworldly faith because Christians await the resurrection of the dead when Christ returns. (“Wrestling Match Over the Resurrection”)

Can we say again with Dr. King, “I have watched many churches commit themselves to a completely other worldly religion which makes a strange, un-Biblical distinction between body and soul, between the sacred and the secular” (“Letter From Birmingham Jail”)?

In direct contradiction to the above claims, Dr. King appears prescient with words written over 55 years ago:

There was a time when the church was very powerful—in the time when the early Christians rejoiced at being deemed worthy to suffer for what they believed. In those days the church was not merely a thermometer that recorded the ideas and principles of popular opinion; it was a thermostat that transformed the mores of society. Whenever the early Christians entered a town, the people in power became disturbed and immediately sought to convict the Christians for being “disturbers of the peace” and “outside agitators.”‘ But the Christians pressed on, in the conviction that they were “a colony of heaven,” called to obey God rather than man. Small in number, they were big in commitment. They were too God-intoxicated to be “astronomically intimidated.” By their effort and example they brought an end to such ancient evils as infanticide and gladiatorial contests. Things are different now. So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. So often it is an arch defender of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s silent—and often even vocal—sanction of things as they are. (“Letter From Birmingham Jail”)

What Is & Isn’t Being Said

First, what is not being said is that all these proponents of the Narrow Spirituality of the Church hold personal prejudice against people of color. That is not even the point of this and the last post. What also is not being said is that there is no proper view of the Spirituality of the Church. There certainly is, but as defined by the Belgic Confession in the last post.

What is being said is that this Narrow Spirituality is a perfect example of systemic and institutionalized racism, regardless of existence or lack of intentional prejudice. As professor Allan G. Johnson often points out, social systems work through paths of least resistance. One may hate racism and make it his daily ambition to love all indiscriminately yet nevertheless operate within social systems—including theological traditions and ecclesiastical patterns—that further reinforce well-worn paths, continuing a racialized system that has accorded advantage and disadvantage along the very same color-line for centuries. And how could we truly expect otherwise? Four hundred years of legal and de facto marginalization for the very sake of exploitation is bound to have borne rotten modern fruits.

The Narrow Spirituality of the Church view, as demonstrated in the last post, is an American interpretation, unknown to our European Reformed and Presbyterian forebears. It was forged not only to coincide with the American experiment of government itself, but more importantly with the deep moral conflicts which arose between the stated Christian belief and ethics of America’s founders and the irreligious and immoral policies that shaped American culture and government from its colonial beginnings. The doctrine came to its acme in the defense of race-based chattel slavery, shielded the institution of Jim Crow from the voice of the Church, and continues to run cover for indifference to social disparities, hostility toward reconciliation activists, and continued church segregation. It is a doctrine crafted for exploitation and has only ever served the socially, politically, economically, and ecclesiastically enfranchised.

Further, it is a doctrine that has always been foreign to the African American Church in America—whether conservative Calvinist Presbyterian or liberal. In fact, it is a doctrine that literally condemns the work of the black church during slavery, Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights movement as sinfully outside the scope of the Church’s mission. It is not surprising that many white Christians are still unable to answer whether such abolitionist and protest movements were even justifiable.

In short, the Narrow Spirituality of the Church is a Procrustean Bed created by those who, as a people group, have never needed the Church to be anything but a Gospel preacher and Sacrament administrator. It must either disjoint or amputate its historically disenfranchised victims in order to offer warmth and comfort within its fabricated boundaries. Even now the NSoC must retroactively condemn the churches of Bryan, Allen, Wright, the Gloucesters, Williams, Paul, Hains, Cook, Bowels, Scott, Gibbs, Randolph, Grimke, Oliver, and every African American church captured by Du Bois’ description.

Is it any wonder that our churches continue to be segregated? Is it any wonder that people of color point to the Reformed and Presbyterian churches as the most hostile to their cause?

Brother, your word burns in my heart.

You should submit these for publication in Opinion section of Washington Post, etc!

They need wider publication.

LikeLike

You are so kind! Thank you so much for reading and I thank God that the time spent proves fruitful. Thank you again!

LikeLike

Indeed, I am impressed by the depth of your research in these articles.

Thank you, so much, for the work you do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are always a great encouragement; thank you, brother!

LikeLike

And this quote:

“We have men sold to build churches, women sold to support the gospel, and babes sold to purchase Bibles for the poor heathen! all for the glory of God and the good of souls! ”

So, so apt, and so applicable to the likes of George Whitefield then, and of ministers today who use the bodies and labors of the church faithful in order to increase their own profit of the gospel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In John 17 Jesus defines eternal life as presently knowing him and the one who sent him in the now. At the end of Matthew 14 Jesus healed. The word is diasodzo which means to bring safely through. That is our call: to bring others safely through.

LikeLike

Ditto to Sharon’s comment. Thanks for your hard work and perseverance in writing these posts.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for reading and for your continued support!

LikeLike

Why am I just now coming across this outstanding piece on NSoC? It was the insulated theology that provided a moral veneer of cover for not only slavery but Jim Crow and opposition to the Civil Rights Movement which was part and parcel of every pre-1970 congregation that fled into the PCA in 1973. What’s possibly even more ethically egregious is the answer to the question, in what demonstrable fashion has Reformed Theological Seminary offered, even up to today, a different theology to its students than the NSoC of yesteryear? RTS continues rendering a paternalistic judgment towards the Black Church while catering it’s fund raising efforts and marketing pieces to portraying a seminary intent on “training” young black men to be faithful to Scripture. The irony. Ligon Duncan continues his failure of ethical courage and theological integrity, not even offering an honest statement of the seminary’s founding nor it’s continued existence for fifty years when in 2016 RTS’s 42 of 43 professors and emeritus professors were white.

LikeLike

What I find interesting is that Evangelicalism has chosen to align itself with conservatism. Not necessarily fire-breathing fundamentalist views on society. But the more benign/malign viewpoint of conserving things as they were in the 1950s.

What a terrible choice of things to conserve. White male privilege. White racism. Economic injustice. Praising the rich and despising the poor. Seeking more and more guns, more and more wars, Cutting education and health and social efforts to create strong people, but instead treating people worth only what they can offer as economic units of productivity. Idealizing the wealthy as an admired group of achievers.

It’s a terrible set of propositions to tie the gospel to.

LikeLike

It is a fatal set of propositions to tie the white gospel to.

LikeLike

Thank you for this! I’ve been preaching 37 years and I’ve seen and felt and grieved over all of this but couldn’t name it or understand it all. Thank you for this…

LikeLiked by 1 person